It’s a Saturday morning and I am standing in front of a wall of skincare products in a bustling Mecca store in Sydney. Every product in this hub of cool glamour seems filled with promise.

I sneak a look at the girl with flawless skin across the aisle. I’ve watched her move between all the cult brands – Drunk Elephant, Glow Recipe, Thatcha, Summer Fridays – using testers, reading labels and discussing the merits of each item with the assurance of a press rep, as her companion nods in interest next to her.

In high school, every geek like me was in awe of a classmate just like her: unblemished skin, smooth hair, and a glow I’m still striving for two decades later. I slink up to her, desperate to ask questions, though I’m aware that no secret of hers will actually help. That’s because the girl I’m in awe of is literally 10 years old. However, like substantial proportion of girls in her age bracket, she is already somewhat of a beauty aficionado. She already has a multistep – and expensive – skin care regime.

Research shows that the global skin care industry is worth an estimated US$186.60bn, and expected to grow by around 6% each year until 2027. In the US, the preteen market – generation Alpha – accounts for a whopping 49% of drugstore skincare sales, despite only 26% of households having a member of this cohort.

They’re also big beauty consumers in Australia: Mecca and Sephora gift cards are coveted birthday gifts; sheet masks are shoved in party bags and used for tween “spa days” and just this month, a primary school child dressed up as a Mecca employee for a dress-up day.

When I was in upper primary school, slip, slop, slapping was the only thing we did to care for our skin. It didn’t get much more extravagant when we got to high school: we learned about beauty by watching our mothers or reading teen magazines, washed our faces with Neutrogena face soaps and “treated” our concerns with Biore pore strips, toothpaste on breakouts, or St Ives apricot scrubs. The closest thing many of us had to a routine was Clean & Clear’s three-step regimen, though some sprung for Clinique if their pocket money allowed it.

My own nine-year-old today, however, has a vast knowledge of beauty. It is a knowledge gleaned from YouTube influencers like ByFannyS, Denitslava Makeup and TheEmmaGrace, conversations with school friends which sends her home asking for $42 lip glosses, blush sticks and face creams with prices I rarely spend on myself. When she brought up niacinamide, a form of the vitamin B3 touted by skincare companies has having anti-acne and anti-ageing impacts, I texted my sisters: “It’s like skipping Strandbags and going straight to Chanel.”

Nine-year-old Molly* is allowed some basics – cleanser, moisturiser, sunscreen, lip gloss – says her mother, Natalia, from Western Sydney. However, Molly dabbles in serums (“she has a hyaluronic acid and niacinamide serum”, Natalia says) and is amassing a collection of other products, mostly by Sol de Janeiro, makers of widely-popular bum-bum cream and a 385ml body wash that costs $43.

Though Molly would love to add some Glow Recipe and Drunk Elephant products to her collection, the answer has been no, on the advice of her mother’s dermatologist and an uncle who’s an industrial chemist. It’s not just a matter of cost (a Glow Recipe toner is $63, and Drunk Elephant’s “whipped cream” moisturiser is $100), though that does raise Natalia’s eyebrows (“I don’t spend that on myself,” she says), but a matter of age-appropriateness.

“I [am] seriously disturbed by how young they start,” Natalia says. “These girls are getting up at 6am to do a full face of makeup and using hair curlers and straighteners before school. They do “glow ups” on video calls together too, [applying face masks, serums, and makeup].

“That’s another appeal of it, they do it together in person or online, or film themselves doing it on social media for likes.”

Chrissy*, also nine, knows “if a product is cool by how many comments and likes they receive on the video”. She is partial to brands like Summer Friday (“I have the whole set,” she says), Rare Beauty and is “obsessed with Sol de Janeiro”, spending approximately $60 a month at Mecca and visiting Sephora for a treat. She is drawn to the packaging, but her mother, Rita, has drawn the line at things like hyraulonic acid an retinols.

“I feel guilty about what I’ve allowed,” says Rita. “I try to say no but find it difficult. It would be challenging to change marketing and influencers. The only way to do that is for me to limit her exposure to them by minimising screen time, which I’m terrible at. I work and find it easier to just let her scroll.”

Although this is at the more extreme end of the spectrum (no other parents interviewed suggested this has been their child’s experience, though I was sent a video of a inner-west-Sydney tween reviewing the effectiveness of under-eye patches for bags and puffiness), psychologists warn that engaging in beauty content on social media could be problematic. Child psychologist Deirdre Brandner worries about the long-term effects of the promotion of beauty messages and products on children as they grow.

“Research tells us that exposure to beauty content [in adults] increases appearance anxiety and negative mood,” she says.

Central to all this, Brandner says, is a need for validation, connection and identity, with children “conforming” to practices out of fear of social exclusion, which can have detrimental effects on their mental health.

Associate Prof Kelly-Ann Allen, from the school of education, psychology and counselling at Monash University, has seen an increased interest in skincare among tweens in her own life. “Of course, the concern that skincare could lead to an overemphasis on unrealistic beauty standards is something we need to consider,” she says, “not to mention the financial aspect.”

However, she suggests, it is important to consider the trend within the context of the particular period of development that tweens find themselves in. “Social influence and peer pressure, a desire to fit in, and a desire to emulate the latest trends and influencers play significant roles. However, an important aspect of this age group is identity formation. I wonder whether skincare serves an important part of self-expression and experimentation, helping them to establish a personal style and identity,” she says.

“While ‘active ingredients’ aimed at older consumers are a concern I see raised by dermatologists, I do wonder if skincare, providing it is safe to use, can have benefits for skill development and hygiene routines in the teenage years.”

Sarah Tarca spent nine years at teen magazine Girlfriend, four of them as beauty editor. Beauty has always been a rite of passage, she says; we’re just moving faster through it.

“In the ‘90s we were all saving for Poppy Shine lipgloss, and later, Lancome’s Juicy Tubes,” she says. “The difference [today] is social media. Now the trend cycle is shorter, and as soon as they get ‘insert coveted thing’ they want the next thing an influencer is spruiking.

after newsletter promotion

“It’s unedited, unregulated and is in constant churn. So rather than waiting another month for a magazine to influence you on what to buy, you’re getting the messaging 24/7.”

Allen says that it is important to remember that the social media influencing tweens is not designed for their age range. “They are viewing products not intended for their age group. Should that be an issue we tackle first?”

‘The truth is tweens need very little skincare’

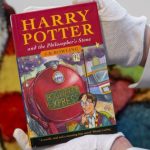

So pervasive is the tween skincare trend that in January Mecca published a post on its website titled “How to tell your tween they’re not ready for retinol”. In February, Tarca penned what she calls a “controversial” opinion piece in her beauty newsletter, gloss etc, offering tips to “parents, aunties and sisters with tweens in their life begging to take them to Mecca”.

“They were overwhelmed and confused, and also caught in a hard place: they want their tween to feel like they belong, but they also want to protect them,” she says. “They also just didn’t know whether these products would be damaging to their tween’s skin, or just their wallets.

“The truth is tweens need very little skincare, if at all, but that is not a sexy sell to a young girl wanting to find her place in the world.”

Randa learned this the hard way when her 11-year-old daughter Miriam* had a reaction to a Vitamin C serum. “She used it once and her face was burning,” she recalls.

“She [also] wanted to use Drunk Elephant because all these young YouTubers were using it and she loved the packaging of the product.”

But it’s imperative to wait before using anti-ageing ingredients like retinol, Vitamin C, AHAs and BHAs, says dermatologist Dr Shreya Andric.

“Most tweens have few, if any, skin concerns and so the use of these products can result in irritation and often cause skin conditions like periorificial dermatitis,” she says. “I have seen young patients who have facial eczema using all sorts of active ingredients on their skin and this has done nothing but worsen their eczema and made their skin very inflamed and angry. It is always harder to treat than it is to avoid.”

Randa “absolutely” believes that the influencer industry needs more regulation – citing the constant marketing and “ever-changing trends”.

Natalia agrees. “The beauty industry is a monster selling us shit we don’t need for decades,” she says. “My concern isn’t any different to what it is with the diet industry or the food industry. It’s about the unrealistic expectations of beauty that can never be met.

“I consciously try to not promote that with her but you’re competing against all this other stuff.”

Tarca suggests mitigating issues by guiding tweens towards age-specific brands like All Kinds, and social media accounts like Lab Muffin, which break down product ingredients. “Regulating [influencer] intake is honestly more helpful, and also knowing what will be OK for them to play with,” she says.

“As a general rule I think makeup can be a fun place to experiment and allow them some agency. Cult lip balms are a great start, [as is] introducing them to a very basic cleanse and moisturise routine so they can still feel like they’re a part of something.”

Outside the Mecca store, 10-year-old Alice*, who agrees to talk to me with her guardian in tow, manages to convince me that I’ve been a little too rigid with my own daughter, who I have essentially banned from all beauty products at nine years old. While Alice expertly talks about serums and bum-bum creams, I think of my own mother’s lack of interest in beauty products and how, despite being aware of the myths and superficiality of the industry, I still feel for the younger me, left outof the beauty world in my formative years.

Back at home, I tell my daughter we can go look at some products together the next time we go shopping, but that I’ll have final say on what (if anything) comes home. And then, because it’s her birthday next month and I’ve already busted her fake-filming a YouTube tutorial with my expensive eyeshadow palette, I hop on the AllKinds website and add a few items to cart.