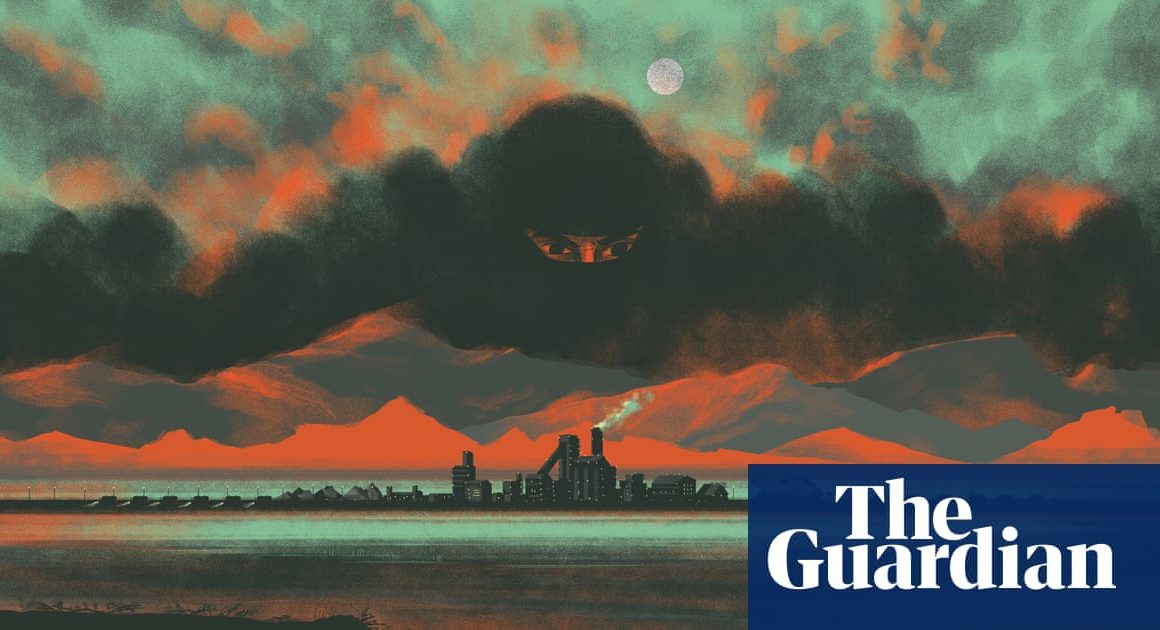

From colourful, enigmatic octopuses, to oysters with their iridescent pearls, molluscs today are as beautiful as they are diverse. But it seems their ancient relatives may have resembled the love child of a slug and a hedgehog.

Soft-bodied creatures are a rarity in the fossil record as their tissues decay rapidly after death. However, researchers say they have found a rare exception in the eastern Yunnan province, in south-western China, in fossils dating to about 514m years ago.

Measuring just a few centimetres in length, the specimens are thought to be the remains of a proto-mollusc.

Called Shishania aculeata, after the eminent palaeontologist Zhang Shishan, and the Latin word for “prickly”, the fossils reveal a flat, slug-like animal covered in hollow, cone-shaped spikes.

While many of the specimens were poorly preserved, with only the creature’s spiny exterior visible, others showed traces of its squishy parts – including a muscular foot on its underside.

“Within those rare occurrences of us having this fossil to begin with, there are a few just pristinely preserved ones that didn’t decay very much while they were being preserved,” said Dr Luke Parry, co-author of the study from the University of Oxford.

Writing in the journal Science, Parry and colleagues report that they also found traces of tiny tubes inside the spines, suggesting the spines once contained microscopic projections called microvilli. These, the researchers suggest, would have secreted a horny substance called chitin, which formed the spines themselves.

While the specimens are somewhat younger than what are thought to be the oldest mollusc fossils, the team suggest the spiny slug-like creature branched off the tree of life before molluscs evolved.

As a result they say the creature could help shed light on what early ancestors of molluscs may have looked like – a longstanding conundrum given the enormous diversity of molluscs and the small number of early mollusc fossils.

Indeed, while it is thought the last common ancestor of all molluscs would have had a single shell, Parry said the new fossils indicated a prickly exterior cropped up even earlier on the family tree. “The new fossil is an extra piece of the puzzle as it shows us what molluscs looked like before they evolved a shell,” said Parry.

The spines, he suggested, were subsequently lost in the branch of the mollusc family tree that gave rise to creatures such as clams and snails and octopuses, but were retained in the branch that gave rise to other molluscs including chitons – marine molluscs that have spines filled with biominerals.

Dr Martin Smith, of Durham University, who was not involved in the work, welcomed the discovery.

“At first blush I might have overlooked the significance of this spiny ‘pancake’,” he said, adding he recalled having seen traces similar to the conical spines in other deposits. If these [features] can be recognised in existing microfossil collections, we might be able to get a handle on the timing of early molluscan evolution, with a much greater resolution than what we currently have,” he said.

Dr Julia Sigwart, of Queen’s University Belfast, also said the discovery of a proto-mollusc was exciting, but noted it was possible spines cropped up more than once during mollusc evolution. “One form that we find in the fossil record doesn’t necessarily mean that all of the other early fossils also looked like that,” she said.