The Piano Lesson is the third film, after Fences and Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, that Denzel Washington has produced from playwright August Wilson’s Pittsburgh Cycle. It’s also the finest. And this time, it’s a family affair.

The film stars Washington’s oldest son, John David, and is directed by his youngest, Malcolm. His daughters, Katia and Olivia, are also involved, as producer and actor in a small role respectively. And as the credits roll, there’s a dedication to the children’s mother Pauletta. Call it projection, but it’s hard not to get sentimental about the kids getting together to grapple with this story. The Piano Lesson is about siblings fighting over the legacy their parents and ancestors passed down to them.

Washington (Malcolm, that is) sets things in motion with some sensationally virtuosic film-making. It’s 4 July 1911 in Mississippi. As the white land owners, descended from slavers, are outdoors, enjoying thunderous Independence Day fireworks, young Black men, led by Boy Charles (Stephan James from If Beale Street Could Talk), crack into one of their antebellum homes. Boy Charles is there to take the heavy, ornamental instrument at the centre of Wilson’s play, a piano with intricate carvings etching his family’s history from slavery to its wood panels.

The scene, as they hoist and slide the piano from the southern household’s living room to a horse-drawn cart outside, is intermittently lit by the explosions in the sky. Flashes of red, white and blue illuminate a thrilling, pivotal moment, as these men take hold of their legacy. Sure, there’s an extravagance to the style, a first-time film-maker flex, but it works spectacularly.

In an adaptation that tends to be confined by its stage origins, mostly taking place in a cramped Pittsburgh in 1936, the moments when Washington can break free – from that setting or even from the material world – aren’t just welcome but exciting. Washington embraces a heightened aesthetic whenever Wilson’s play, about a brother and sister at odds with what to do with the piano, leans into surreal and ethereal. But a better measure of his budding talent are the rich textures he lends intimate scenes. There’s a gentle caress between two actors, where he holds the anticipation for a kiss just long enough that it left me gasping. And then there’s the way he frames Danielle Deadwyler in the smallest moments against earthy hues. As Boy Charles’s daughter Berniece, she’s a smouldering presence, who captivates like the centre of a painting come alive.

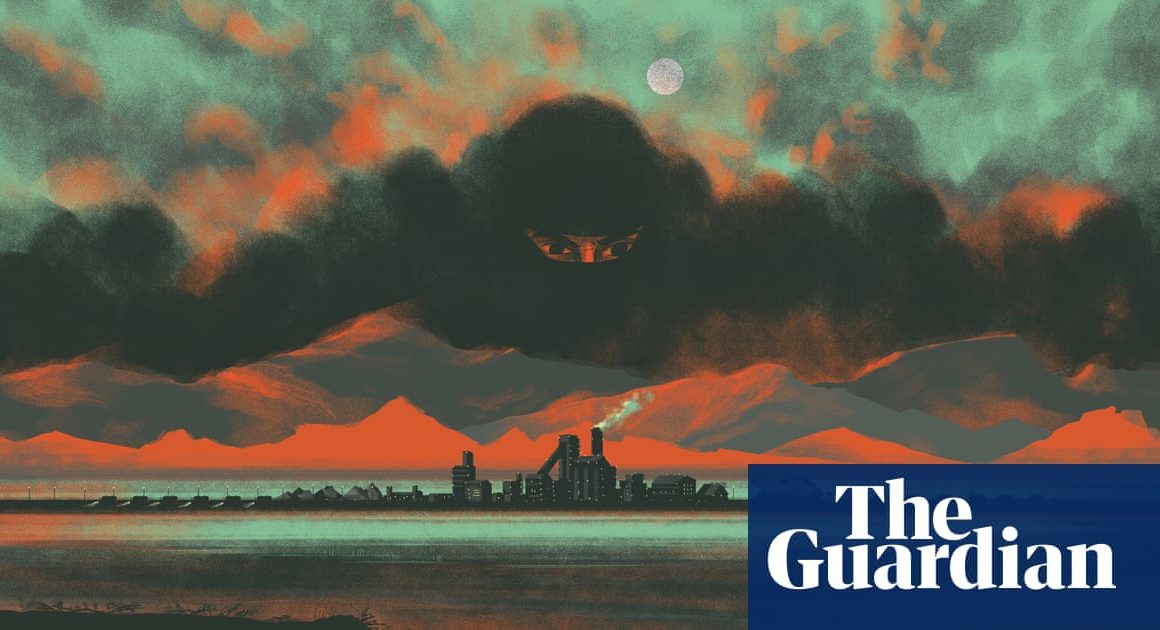

Deadwyler, the unsung star of Till, famously robbed of an Oscar nomination nearly two years ago, is the only actor in the main cast who was not involved in The Piano Lesson’s 2022 Broadway revival. The returning members are led by John David Washington as Berniece’s excitable brother Boy Willie, who arrives in Pittsburgh with a truck full of watermelons to sell and news that another member of the Sutter family, who enslaved their ancestors, has fallen down a well. Sutter’s land is up for grabs. Willie has it in mind to sell the family piano for the cash, which Berniece is fiercely against. She also suspects that Boy Willie pushed Sutter down the well. Maybe that’s why the decaying white man’s spectre is now haunting their family in chillingly fun sequences that take notes from recent elevated horror aesthetics.

As Boy Willie, a persistent hustler, Washington is wound up and often speaking as though he’s still in the theatre trying to reach the audiences at the back of the theatre. Samuel L Jackson, who played Boy Willie in the original 1987 production, has a far better time translating his performance, and its rhythms, to the screen. He’s the practical Uncle Doaker, who takes a comically neutral but not informed stance to arguments over the piano and the ghosts shackled to it.

Ray Fisher, the embattled Justice League star who spoke publicly about being at odds with Joss Whedon and Warner Bros, is here as Boy Willie’s friend Lymon, a fella both dotish and pure of soul. And finally, Michael Potts revives his winning performance as Wining Boy, Doaker’s brother, who finds warm and at times outrageous humor, not to mention relief from his sorrows, at the bottom of a bottle.

Striking that balance between the comedy and the drama in Wilson’s play is a tricky proposition, and the bigger emotions in The Piano Lesson tend to feel drowned out by the laughs. This is an emotionally complicated story, after all, about two people struggling with what to do with their family’s trauma, and where to put their pain.

You can’t spell piano without pain. Willie Boy’s stubborn insistence to sell the family heirloom is a bid to free himself from the past – its emotional burden and the legacy of slavery – and use that money to take hold of a future where he is his own master. For Berniece, on the other hand, who protects the sacrifice of those who came before her, is emotionally stuck in the past. She’s mourning a husband and struggling to find her way forward.

The tension between them never quite takes hold, even when their emotions boil over, which Washington, the director, manifests visually during an amusingly chaotic ghostly reckoning, achieving a different kind of catharsis. There’s a struggle throughout the movie to marry the human emotions to the surreal and supernatural spectacle.

But Washington nails it in one scene, when the men are gathered around a table in conversation, and then break into the prison song Berta Berta as the film for a brief moment becomes a musical. They stomp their feet, echoing the clanging of the railroads, as the camera dances between them. There’s real soul to this moment, which is somehow both grounded and elevated, where men shackled by circumstance are singing to the heavens.