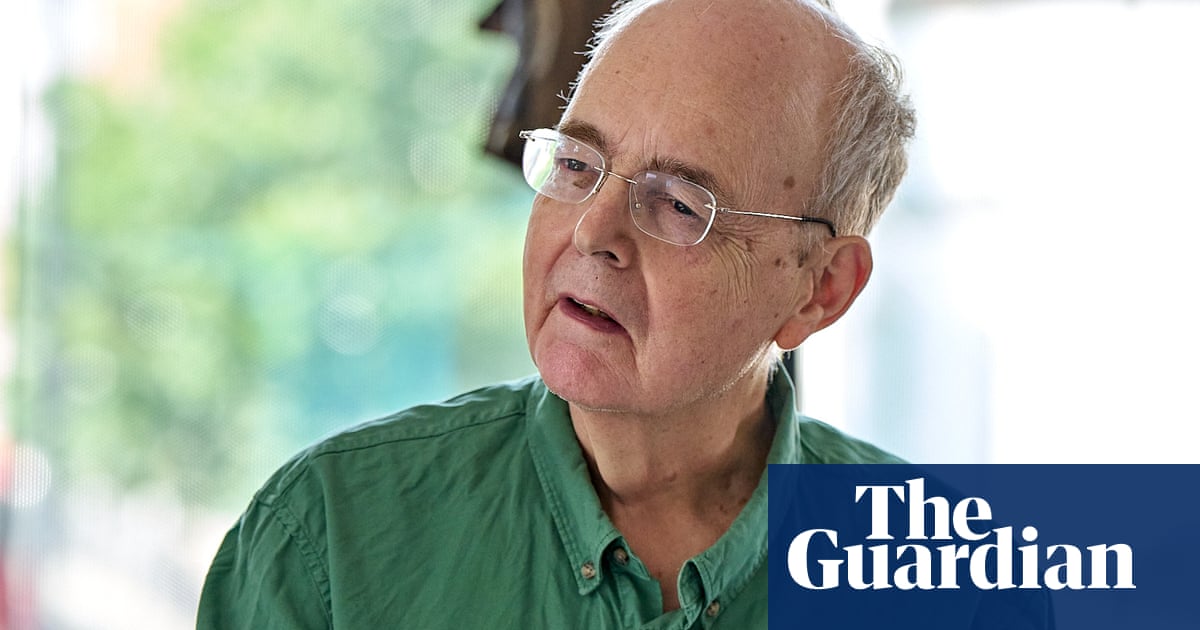

With the world premiere of The New Real, David Edgar achieves the rare distinction of having at least one play performed by the Royal Shakespeare Company in six successive decades, starting with Destiny in 1976. However, 2024 is summed up for the dramatist by a line in one of the company’s most performed plays, Hamlet, when Claudius, addressing good and bad news, describes himself as having “one auspicious and one dropping eye”. Early in the year, Edgar suffered an eye injury that forced emergency surgery and slow recovery of full function.

“It’s getting better but it’s worse when I’m tired,” says the dramatist, 76. And he has reason to be fatigued. After a six-year gap since his self-performed memoir monologue Trying It On, he is currently commuting between rehearsals of two new plays. The New Real is about American and British spin doctors working on an eastern European election 20 years ago who stumble on the template for Trumpism and Faragism. It follows the opening, at the Orange Tree theatre in Richmond, of Here in America, a bio-drama set in 1952 in Connecticut, where the playwright Arthur Miller and his regular director Elia Kazan meet before the latter’s testimony to Senator Joe McCarthy’s inquiry into “Un-American” communists in US showbiz. The evidence broke the men’s friendship and inspired Miller’s great play about ruinous accusation, The Crucible.

The new works prompt a question that invites immodesty. What do the major plays of William Shakespeare and David Edgar have in common? A trained journalist (he worked for the Bradford Telegraph & Argus from 1969-72), Edgar is skilled at spotting and evading a potential gotcha: “So. What you want – instead of comparisons with Shakespeare, let me compare myself to James Graham and Peter Morgan –”

“No. It’s not a trick question. There is an actual comparison between you and Shakespeare. A large number of your major plays are set –”

“Abroad! Yes, very good. That is interesting.”

The New Real is his fourth play – after The Shape of the Table (1990), Pentecost (1994) and The Prisoner’s Dilemma (2001) – set in a fictional post-soviet eastern European country unnamed on stage but which the playwright jokingly thinks of as “The People’s Republic of Edgarvia”. Here in America is his fourth play set in the US after the paired plays Daughters of the Revolution/Mothers Against (2003) and a TV drama, Buying a Landslide (1992). His epic Maydays (1983) – exploring the oddity that many architects of Thatcherism were ex-communists – featured pivotal scenes in the US and eastern Europe.

Most playwrights stay close to home. So did Edgar consciously choose to travel? “I spent the year 1978-79 on a scholarship in the US and that was very formative to much of what I wrote afterwards. For anyone who was 20 in 1968, that year is going to be their origin myth. And, in America, the impact of that is going to be at its most extreme – the assassinations [of Robert F Kennedy and Dr Martin Luther King] and the riots at the Democratic convention at Chicago. And it was also the cold war so, yes, I think I did consciously write about the opposing superpowers.”

More recently, during arguments about the “authenticity” of narratives and actors, there have been suggestions that plays about America and eastern Europe would be better coming from residents of those countries rather than of Birmingham, Warwickshire, where Edgar lives with writer Stephanie Dale, who he met and married after the death in 1998 of his first wife, local politician Eve Brook.

“Look, I think there will be eastern Europeans who see The New Real and criticise it. I haven’t spent much time in sub-Saharan Africa but, if I did, I think I could write about its politics.” But many theatres and critics would now say he couldn’t. “No. You’re probably right.” So how does he feel about the experiential qualification? “I do challenge that. If you can’t write about something you aren’t, then – it’s crude to say – you end up writing solo shows.” As he did in Trying It On? “Yes. Once. But the whole business of theatre – acting and writing – is based on the idea that you can think yourself into someone else’s shoes. If you can only think yourself into the shoes you happen to be wearing, it makes the business of creating fiction impossible. So I have no choice but to challenge that. Most of our experience is actually second-hand – from reading, watching films, observing others, asking questions. All you can ask from someone not writing from their own experience is that they find out.”

He catches himself at risk of defending veteran’s privilege: “I hope I’ve always not only campaigned for but enabled diversity in the theatre. But on the other hand you wouldn’t be human if you didn’t feel it would be nice if your plays went on. The other thing is that in Britain – which is largely due to subsidy – we have allowed people to have whole life careers which doesn’t happen in America.” Arthur Miller came to the UK when Broadway wouldn’t put his plays on. “Yes. And I think that was a benefit to the theatre. When I argue that it’s sad theatres don’t have a ‘stable’ of writers, the counter-argument is that a ‘stable’ is exclusive. Of course it will be if that’s all there is. If it’s all ‘stable’, you restrict entry. But if it’s all new writers, no one has a career. So it’s a balance that I think is worth preserving. And that will be complicated for a while because the older writers will tend to be white men.”

Under strict rules of live it to write it, Here in America could only have been written by Arthur Miller or Elia Kazan. It is based on reading their own words and others’ about them. “I started it in the mid to late 2010s. And I think it’s become more apposite now, in the sense of McCarthyism. [There is] a more paranoid, polarising politics than there has been since the 50s in America. In the US, books taken out of libraries. Cancel culture, which is obviously complicated because the left has taken that up as well. But you also have a political movement built around accusing liberals of being communists.”

Opposite the south London pub where we meet after rehearsals, there is a Voltaire Road. Edgar quotes a saying often attributed to the French philosopher though disputed: “I disapprove of what you say but will defend to the death your right to say it.” He adds: “I don’t think many people would even understand that now.”

Political tolerance also struggles when people are driven to extremes by their ideologies. During the recent urban unrest, it was hard not to think of Edgar’s Destinyand Playing With Fire (2005), plays about racial tension in Britain. Both were criticised for exaggerating the power and influence of rightwing extremism but he must feel vindicated now?

“Yes. Destiny keeps being revived because the far right keeps coming back. I think what Destiny said was: The National Front was a neo-Nazi party but there was something going on socially that was the soup in which it bred. And, without identifying any group as Nazis now, I accept there is still the issue of how you confront the underlying discontent that allows that type of politics to multiply. What interests me is that – and I think in both cases due to social media – the riots spread very quickly but also died very quickly. There was a huge community counter-movement. But the riots reminded us that ideas have consequences. If you are constantly criticising not just immigration but also immigrants don’t be surprised at what happens.”

He is also critical of the party to which he remains broadly loyal: “One of the things The New Real is about is that – in the split between New Labour and Old Labour it was New Labour that filed for divorce. There’s a line in Here in America: ‘I didn’t leave the left, it left me.’ One of my themes is that the working-class left didn’t leave the Labour party, the Labour party left it. And partly from the conviction there was nowhere else for those voters to go. But that’s always a mistake.”

Still hanging is the comparison he planned to make with James Graham when we discussed Shakespeare. He explains: “What audiences seem to be after now is a confrontation that really happened and had high stakes for the two people involved. And they become a metaphor for a debate in society. Peter Morgan started it in Frost/Nixon and The Deal and The Crown. James Graham does it in Best of Enemies and Dear England. Both of my new plays – which happen to have American central characters – are about such confrontations.”

And so an older playwright learns from the younger generation. After the accidental double-bill, he plans a holiday. And then? “I’m writing a book about my life in political theatre. Which I hoped to finish this year. But partly because of the injury – and also these two plays – that has gone back. I don’t have a new play idea … Steph and I have a bucket list of things we want to do. And the eye has been a slight warning that bits of you that are quite important can go wrong.”

-

Here in America is at the Orange Tree, London, until 19 October. The New Real is at the Other Place, Stratford-upon-Avon, 3 October-2 November