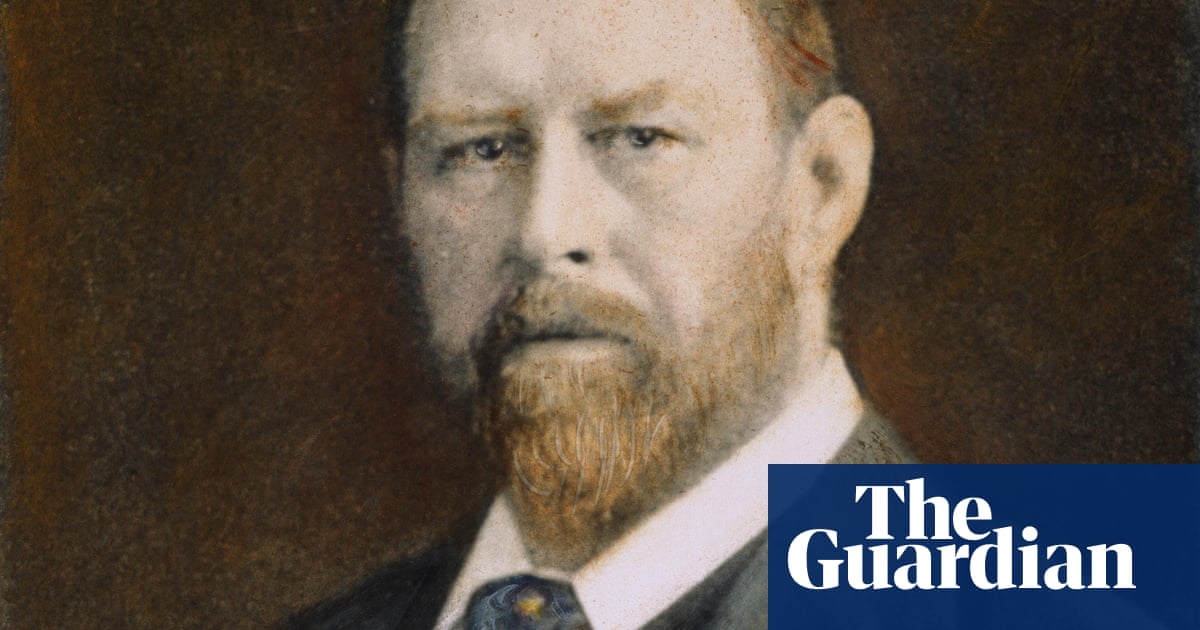

In a Dublin library once frequented by James Joyce and WB Yeats, beneath a turquoise and white domed ceiling and surrounded by oak shelving, Brian Cleary stumbled across something by Dracula author Bram Stoker he believed no living person had ever read.

Cleary, who had taken time off from his job at a maternity hospital after suffering sudden hearing loss, was looking through the Stoker archives at the National Library of Ireland when he came across something strange. In a Dublin Daily Express advert from New Year’s Day 1891 promoting a supplement, one of the items listed was “Gibbett Hill, By Bram Stoker”. He had never heard of it, and went searching for a trace. “It wasn’t something that was Google-able or was in any of the bibliographies,” he said.

Cleary tracked down the supplement and found Gibbet Hill. “This is a lost story,” he realised. “I don’t think anyone knows about this.” The story follows an unnamed narrator who runs into three children standing by the memorial of a murdered sailor on Gibbet Hill, Surrey, which is also referred to in Dickens’ 1839 novel Nicholas Nickleby.

Together, the four walk to the top of Gibbet Hill. Distracted by the view, the narrator loses sight of the children. He takes a nap among some trees, and wakes to see the children a short distance away, before a snake passes over his feet towards the children, who appear able to communicate with and control the snake. Later, the children attack the narrator. The story culminates with the snake wriggling out of the narrator’s chest, gliding away down the hillside.

Cleary approached Stoker biographer Paul Murray to authenticate the story. Though Murray was excited by the finding, he wasn’t surprised – he had already discovered three similar stories, so he knew there was more Stoker material out there. But “as I learned more about the story I became more and more intrigued, because it was published – and almost certainly written – in 1890,” he said. “That’s the year that Bram Stoker begins working on Dracula”.

The quintessential gothic horror novel “didn’t come out of nowhere”, said Murray, who has been researching Stoker’s development from the mid-1870s to Dracula’s publication in 1897. “To me, Gibbet Hill was a very exciting new piece of that jigsaw. It fitted very well into my theory of the long gestation of Dracula. And so this seemed to me to be a kind of waystation on that journey of over 20 years that Stoker spent evolving his fiction.”

Gibbet Hill has parallels with Dracula. There is the gothic imagery, a trinity of malevolent characters, and a description of eyes that “gleamed with a dark unholy light” – anticipating the eyes that “blazed with an unholy light” in Dracula.

Another thematic parallel is that of “reverse colonisation”, said Murray. In Gibbet Hill, two of the children are Indian. In Dracula, you have “the Count coming from Transylvania, which is on the borders of the known world at that time, coming back to threaten England”. While Dracula might be read as a critique of British imperialism, it is also a “reverse colonisation fantasy inviting the British to see themselves as potential victims”, wrote David Higgins in his book Reverse Colonization.

A book featuring the story, commentary and artwork by Paul McKinley is now being published by the Rotunda Foundation, the official fundraising arm of the Rotunda hospital where Cleary works. All proceeds will go to the newly established Charlotte Stoker Fund – named after Bram’s mother, who was a campaigner for deaf people – to fund research on risk factors for acquired deafness in newborn babies. An accompanying exhibition is showing at Casino Marino in Dublin, and the first public reading of the story will take place at the Dublin city council Bram Stoker festival.

after newsletter promotion

It is “not very often” that a discovery of such magnitude is made, NLI director Audrey Whitty said. Yet she emphasises that “anybody’s capable” of a find like Cleary’s. “Who knows what lies undiscovered in any national library in the world?”

-

Gibbet Hill by Bram Stoker is published by The Rotunda Foundation on 26 October. Paul McKinley’s exhibition Péisteanna is now on at Casino Marino, Dublin. More information on the Dublin City Council Bram Stoker festival can be found at bramstokerfestival.com