A flash of Technicolor fills the screen, as four women spin and glide in perfect unison. The bouncy crunch of drum machines collides with slick, soaring vocals, as the women then jump over one another’s heads. “I broke my ankle doing some of this stuff,” says Stacy Francis of the lively music video for You (You’re the One for Me) by her group Ex Girlfriend. “Some of what we were doing was unheard of at the time. There wasn’t anything like that before we came along.”

Populated by the likes of En Vogue, SWV, Pebbles, Karyn White, Jade, Xscape and others, this was new jill swing, the female counterpart to new jack swing, which exploded in the late 1980s and early 90s by fusing US hip-hop with pop and R&B. It would go on to shape R&B as we know it but came at a cost for many of the women involved. “It was an exciting road,” says Francis. “But it was also rough and heartbreaking. There was a lot of exploitation.”

The scene is now being revisited in a new compilation put together by Saint Etienne’s Bob Stanley. “It seems crazy that these two things were so separate,” says Stanley of the now permanently interlocked genres of rap and R&B.

“Hip-hop was still not completely respected at that point as an art form,” explains Tara Kemp, whose 1991 US Top 10 hit Piece of My Heart features on the compilation. Pop radio stations demanded a version with its rap removed. “A lot of people still didn’t think hip-hop was music,” Kemp says.

“It was like when rock’n’roll came around and your grandparents would be like: ‘It’s not gonna last!’” recalls Shireen Crutchfield, who was the lead singer of the Good Girls, a group who were marketed as the Supremes of the new movement. “New jack swing was definitely a generational thing – a distinct departure from what was before. Our manager wanted us to stay away from it because he was a lot older than us.”

The person who changed that mindset was producer Teddy Riley. “There was a snobbery around rap,” recalls Joyce Irby, one of the more experienced artists on the scene. In the early 80s she released her own rap track, A Wild and Crazzy Song, and joined pop-R&B group Klymaxx before becoming a solo artist on Motown Records. “But Teddy’s stuff was so musical. He really could incorporate and blend hip-hop with traditional R&B so that there were elements the old-school musicians could respect. His stuff was exquisitely done.”

Riley is the unquestionably the godfather of new jack swing: he was the force behind boybands Guy and Blackstreet, and produced early scene hits by Bobby Brown and the Get Fresh Crew. “At the time, nobody was coming with the authentic, eclectic, offbeat fusion styles,” he said in 1987. “We gave R&B a new lifeline.”

However, while Riley’s contributions to the genre have long been celebrated, along with producers such as Full Force, LA Reid, Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis, Babyface and Bernard Belle, Stanley wanted to showcase the women from the era. “These groups were definitely treated as second class by the record companies and producers because they were women,” he says. “But they really laid the groundwork for a lot of the female R&B acts of the late 90s and early 00s and productions by the likes of Timbaland, Missy Elliott and Rodney Jerkins – basically, some of the most incredibly extreme music to become commercially successful in history.”

New jack swing was also known as swingbeat and on Irby’s track on the compilation, She’s Not My Lover, you can hear why. “I loved big band swing,” she says. “You can hear the influence in the horn lines on that song.” She worked as a co-writer and co-producer with another scene mainstay, Dallas Austin, and cites Motownphilly by Boyz II Men, “a track that he cut and then I edited. I was like: ‘You’ve got to put the real swing in from back in the day and merge that.’”

This nuanced music became a phenomenon, “a huge wave just taking over everything and everywhere,” says Crutchfield. Established mainstream artists such as Boy George, Diana Ross and Quincy Jones all had a go at new jack swing; affiliated films came out such as New Jack City, with a multimillion-selling soundtrack. House Party, starring new jack swing duo Kid ’n Play, even gave the scene its own hairstyle: the hi-top fade.

As the industry latched on, a lot of the women featured on Stanley’s compilation were spotted and signed up while they were young. Crutchfield, who was in high school and dancing on the TV show Soul Train, was signing a deal to Motown by the time of her 18th birthday. Francis was in a Broadway show at 16, then signed and in Ex Girlfriend by 18. Irby was spotted years earlier, aged 16, by George Clinton, while hanging around on the loading bay outside gigs, playing her bass guitar. However, while Clinton was supportive and nurturing, many of the others faced much more difficult situations.

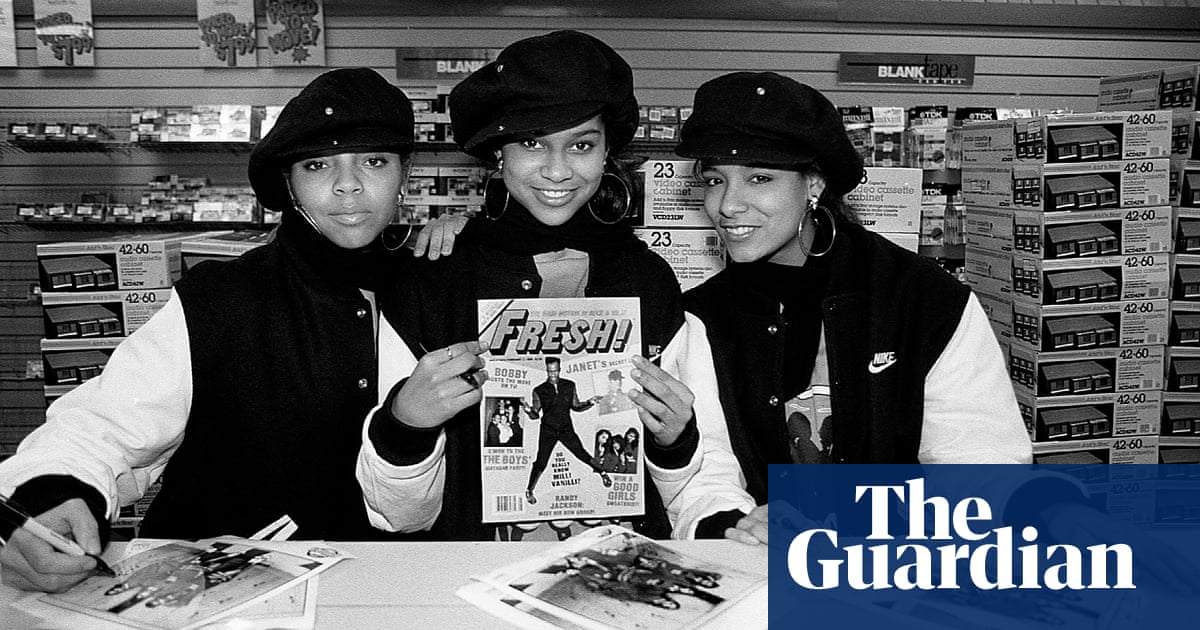

Photograph: Paul Natkin/WireImage

“The whole industry is very toxic,” says Kemp. She was signed to Giant, a label run by Irving Azoff, who was best known for managing the Eagles. “He had wanted it to be a rock label but he hadn’t had any hits,” she recalls. “They didn’t really sign me to be an artist because he didn’t care about this type of music. He just needed a hit.” (When contacted via his publicist, Azoff did not respond to multiple requests for comment.)

Her 1991 debut single, Hold You Tight, duly reached No 3 and was certified gold, but she faced hapless label ideas as they tried to rebrand her. “Their vision was for me to be wearing a black lace teddy carrying an Uzi and acting like a Black girl from the ghetto,” she says. “As someone who came up legitimately in R&B music, I was never about pretending to be something I’m not. It was really cringeworthy and horrible. When I heard that, I was like: ‘I’m out of here. This is not gonna fly.’”

Meanwhile, despite Motown’s girl group pedigree, the label were struggling with the Good Girls. “I don’t think they knew what to do with us,” says Crutchfield. “We weren’t appreciated as artists; we could have done so much more.” The group split in 1993.

Francis says Ex Girlfriend “were four young women from the ghetto who were taken full advantage of. If you look at any group on that compilation album and you go: ‘Hey, what happened to that person? Where are they?’ Most likely, they signed the most horrific record contract. Which is what we did. We didn’t have anybody that cared enough about us to say: ‘Wait for a lawyer.’” (Warner Music could not make anyone available for comment.)

However, despite the bruises from their experiences – Kemp alleges she ended up blacklisted from the industry, couldn’t get a deal, and was “literally not allowed to play” because of egotistical interference from her label after she negotiated an exit from it – there’s a huge pride in the music they presciently created. “We need those phenomenal songs from these talented women out there,” says Francis. “In many ways this is very bittersweet for me but to have our fingerprints on that new jack swing era and be pioneers of that – come on, it’s just epic. There has been a lot of hurt and healing to go through but no matter what you experience in life, no matter how many people come along and take advantage, that music still lives on. Art always wins.”