No one knows exactly what happened in the final moments of Vadim Stroykin’s life.

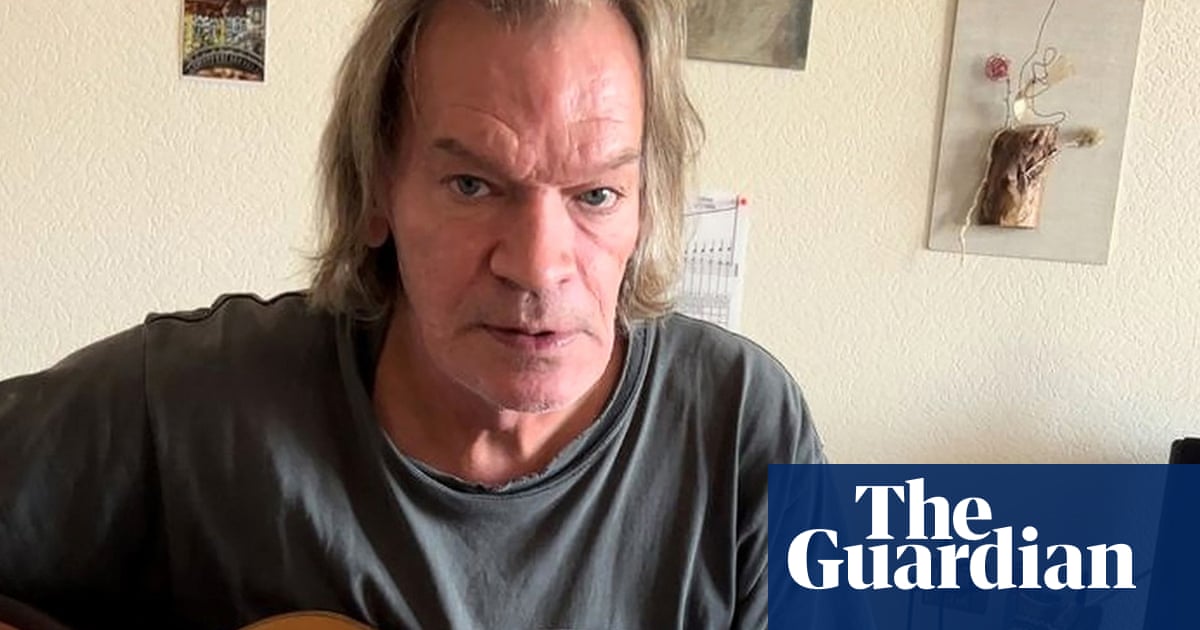

The 59-year-old Russian singer-songwriter’s vibrant career came to a sudden end on 5 February when a team from Russia’s security services arrived at his cramped ninth-floor St Petersburg flat at 9am. They were investigating him for what has become one of the gravest offences in today’s Russia — donating to the Ukrainian army.

According to Russian media reports citing government sources, Stroykin excused himself to the kitchen for a glass of water, opened a window and fell to his death in an apparent suicide. A passerby discovered his body below.

Some of those who knew him best, however, have questioned if he would have taken his own life.

Stroykin was remembered by a dozen friends interviewed by the Guardian as a charismatic and idealistic eccentric. He never concealed his disdain for Russia’s war in Ukraine, even as speaking out became increasingly perilous.

“This idiot [Putin] declared war on his own people as well as a brother nation,” he wrote on social media in March 2022, a month after the invasion began. “I don’t wish for his death; I want to see him tried and put in prison.”

Philip Buckup, a close friend who had known Stroykin for more than 30 years, said he had “an acute understanding of right and wrong”.

Friends describe Stroykin, who grew up in the Urals, as a passionate mountaineer who always had an independent streak.

In the final years of the Soviet Union he was expelled from university for participating in an anti-Soviet demonstration and forcibly conscripted into the military. He later gained recognition as a self-taught bard musician, a genre linked to the Soviet cultural thaw of the 1960s and the rise of allegorical songs as a means of expression. He also taught students in Russia and online around the world.

Buckup said Stroykin had lost some of his positivity and spark after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. He spoke of feeling isolated and depressed on social media and in conversations with friends, and he turned to drinking.

He considered fleeing to Europe at one point in 2022, another friend in Germany recounted, but realised he might not be able to secure the necessary documents to stay.

Despite his growing despair, few of his longtime friends accept the reports in Russian media that he killed himself. Instead, they say something more sinister took place.

“Vadim is not the type of guy who would do it himself, I don’t believe the official version at all,” said Buckup, who last spoke to Stroykin in January. “He was very confident in his views, he would not be afraid of jail. I think the police pushed him out.”

Florida Vovsi, another old friend of Stroykin, said she didn’t believe he would have killed himself either and blamed the authorities for his death.

“He had big plans, he loved life so much, it is hard for me to believe he would do it,” she said. “We don’t know what happened, but I think they ‘helped’ him out.”

after newsletter promotion

Russia has a long history of prominent executives, outspoken Putin critics and other high-profile figures dying in mysterious circumstances, some in falls from windows. Some cases are suspected assassinations, and others remain ambiguous. Few are believed to have been suicides.

Stroykin was one of the thousands of unknown anti-war Russians who decided to stay behind in the country but continued to speak out. Some have been arrested and later died in jail in what the authorities said were suicides. For others, such as the concert pianist Pavel Kushnir, who staged an unpublicised hunger strike, it took days for the world to learn of their deaths.

Alexander Cherkasov, a board member of the Russian human rights group Memorial, said the persecution of anti-war dissenters often comes to light too late.

Journalists and civil society typically learn of prosecutions only after court rulings are handed down — verdicts that are delivered without explanation or justification.

Stroykin’s body has not been released to his family, his friends say, making it harder to establish the cause of his death.

For many of his friends though the conclusion is clear. The state bears ultimate responsibility for his death because he had the courage to speak out against a brutal and unprovoked war.

“There is no place for an honest man like Stroykin in modern Russia,” said Vovsi.