The pioneer African American fashion model Renauld White attributed his unexpected, more than 50-year career to a football coach, Tom Higgins of West Side high school, in his native Newark, New Jersey.

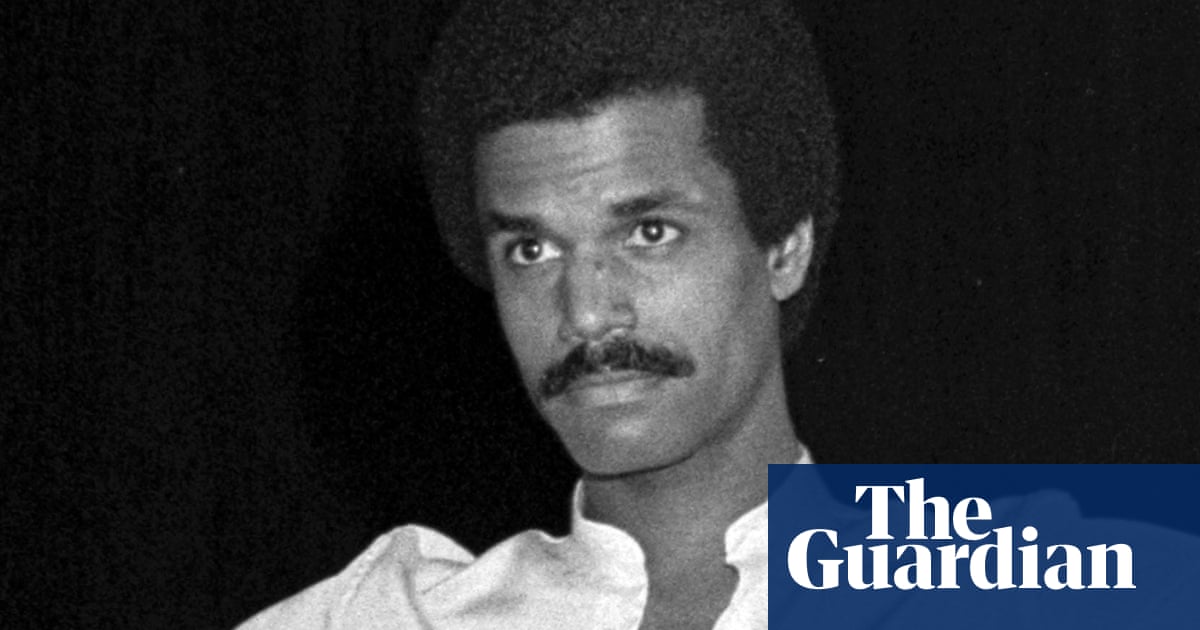

White, who has died aged 80, recalled how he had been tall but chubby when Higgins ordered him on to the school team, and thus kickstarted his lifetime’s dedication to fitness and aspiration to a bigger world. This he achieved, modelling for the American designers Bill Blass, Ralph Lauren, Donna Karan, Calvin Klein, Jeffrey Banks and Stephen Burrows; and becoming a glamorous figure in Jet and Ebony, glossy magazines for black readers, and in 1979, a cover star for Condé Nast’s then still very white men’s magazine GQ. He was a favourite face – animated, perpetually handsome – of photographers from Horst P Horst in the 1970s to Steven Meisel, who shot him for Dolce & Gabbana last year.

Growing up, White had barely known that men modelled. His style inspirations were the young Marlon Brando, the smooth cool of black close-harmony singers, and later the self-possession of the activist Malcolm X. He had to take paying work immediately after school – to support his divorced mother – as a 9 to 5 clerk with the telecoms company Western Electric, which left evenings free for business courses via Rutgers University. Socialising there, he encountered a Fashion Institute of Technology student, Stephen Burrows, and a white model, Jeff Blynn. They became the nucleus of a group that remade its own fashion from local thrift store finds, and its own entertainment, dancing to Latin music at weekends at the Palladium in New York City.

In 1968, when White was confident enough to buy himself bell-bottom pants, Blynn sent him off to an open casting call at Bill Blass in Manhattan. He was rejected because he had no formal representation, so he looked up the address of Eileen Ford’s leading model agency, walked across town and presented himself, a non-standard size in his crazy dance-hall finery, with a large Afro and a sport-scarred nose. White got as far as the head booker, but she balked at his complete lack of experience, and suggested he try Wilhelmina Cooper’s new breakaway agency.

Another address to look up, another few blocks walk. As White told the fashion blogger Jeffrey Felner long afterwards, he expected another rejection for being black. But he told himself this was the US north – not the south, where there had recently been race riots – “so I marched right in and claimed that I was from the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) and was checking to see how racially diverse the agency was”. He promised picketing next day if it wasn’t.

Staff corralled him in a private office, discovered he wanted a break, and gave him the chance to come back with cut hair, quieter clothes and a calmer manner, and reapply. He slept on a friend’s couch in Manhattan overnight, went to the barber, bought a new outfit, and returned. Cooper’s signed him up on contract. The new chamfered grooming, especially the Afro trim, earned him regular work and a show debut for Bill Blass in 1970.

Like the former black model Richard Roundtree, who was cast instead of a white star to lead the movie Shaft, which premiered in 1971, White looked super-sleek when contrasted with the middle-aged middle-American pale males who had burst into funky hair and florid sideburns all around. (White did grow a 30s movie-star suave moustache; and did adverts for Vitalis hair tonic, for a white market.)

So White’s style ran five years ahead of mainstream masculine looks, black or white. He did daily gym workouts for the rest of his life – mostly karate – but with the chief aim of flexibility and easy movement, not 70s muscle. He wore a dashiki shirt or a camel steamer coat with equal slight amusement, and that GQ cover (where he was only the third black man to appear, preceded by Sammy Davis Jnr and the Swiss-Nigerian model Urs Althaus) brought him many magazine spreads as classic menswear triumphed in the 80s.

He was the face above the collars of Arrow shirts, and of commercials for Black Tie cologne. The singer Aretha Franklin saw him in the latter and and invited him to be her escort to gala events, which he continued to do for the next decade, in what he called his “pillar of coolness” mode. He did a little acting in off-Broadway theatre, and in television, including the soap Guiding Light.

The germ of White’s style came from his father, Robert, a truck driver, who was always smartly turned out when off-duty, and his mother, Maybelline (Scott), who had modelled hats. He repaid Coach Higgins’ investment in his potential by mentoring young black models, encouraging them to save their brief peak earnings in order to finance their futures, and by giving talks in schools and university demystifying glamour: what worked, he said, was showing up ready, and perseverance.

Of White’s three brothers, Colin survives him.