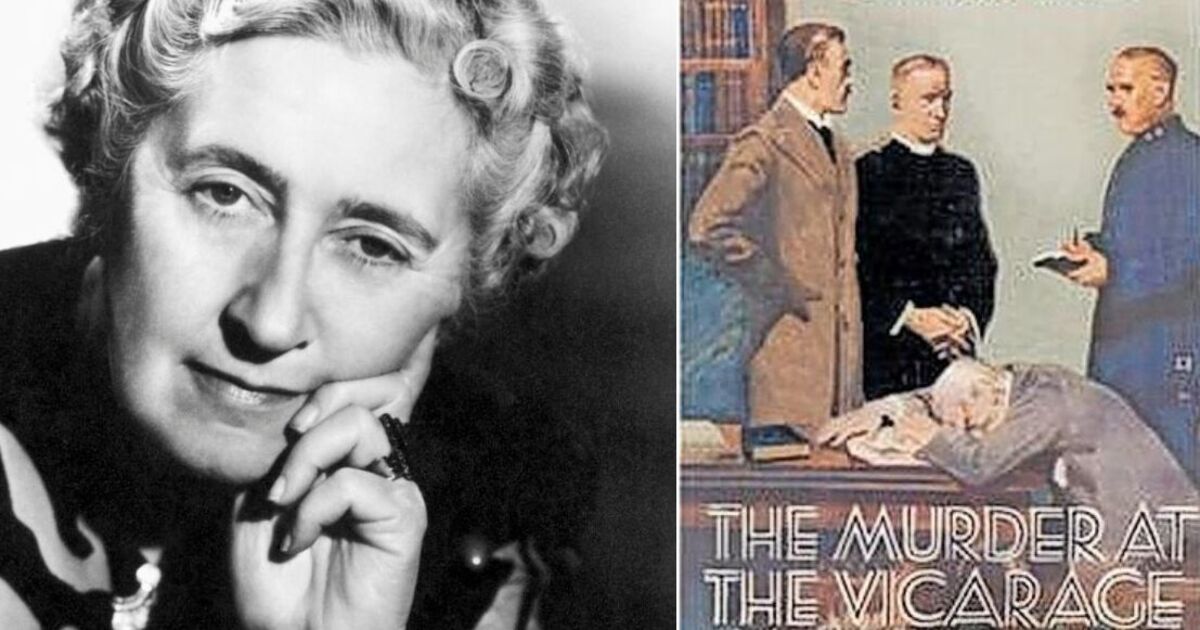

For nearly a century, Agatha Christie’s Miss Marple has kept millions of readers and TV viewers entranced by her remarkable detection skills. However, both St Mary Mead’s finest and her creator have had challenges along the way.

Today, there is no end of “cosy” crime fiction that seems to be inspired by much of what happens in Miss Marple mysteries. Yet there was never anything particularly cosy about the character – or the violent and vindictive murders themselves.

When Miss Marple first appeared in a series of short stories in late 1927, it was at a tumultuous point in Christie’s life – the previous year saw the death of her mother, a request for a divorce from her first husband, Archie Christie, and her highly publicised disappearance to a spa hotel in Harrogate at a time of high stress.

So she arrived in Christie’s imagination just as the author realised she had to become a self-sufficient woman, and so she needed to ensure an income.

Seven years after the publication of her debut novel, The Mysterious Affair at Styles, Christie finally considered herself to be a professional writer, rather than a woman with a successful hobby. As this newly independent woman, perhaps it’s no surprise that Christie created a character who did not depend on a man (although in the end Christie herself remarried, with the archaeologist Max Mallowan in 1930).

Although Miss Marple, whose first appearance in a novel was Murder At the Vicarage in 1930, has several relatives, she never married and, as far as we can tell from the original stories, had only had the occasional flirtation with young men in her youth.

Christie confessed that she had never really thought about Miss Marple’s earlier life and that she considered the character to have been “born” at the age of 65 to 70.

Nevertheless, when reminiscing in later years, Miss Marple fondly recalled how her mother had disapproved of the affections of a “very unsuitable young man”, despite the initial heartbreak. Miss Marple confesses that when she came across the young man again years later, she realised that “really he was quite dreadful!”.

Young Jane Marple’s mother saved her daughter from a life of unhappiness: Miss Marple does not need a husband to feel fulfilled. Much of the remaining character of Miss Marple was inspired by elements of Christie’s own elderly relatives, including her grandmother, and her collection of friends, whom the author dubbed the “Ealing Cronies”.

Christie clarified that Miss Marple “was far more fussy and spinsterish than my grandmother ever was. But one thing she did have in common with her – though a cheerful person, she always expected the worst of everyone and everything, and was, with almost frightening accuracy, usually proved right”.

This cynicism is one of the most enduring aspects of the often very dark world in which Miss Marple lives. So given her rather old-fashioned origins, as a woman of Victorian England, why is it Miss Marple has endured?

As recently as 2022, a new collection of Marple stories from contemporary female crime writers became a bestseller, showing there is still an appetite for Miss Marple’s somewhat traditional ways. But perhaps the ongoing interest in the character is because, despite her origins, Miss Marple’s own perspectives aren’t particularly old-fashioned. Her understanding of human nature is universal, whether it takes place in England of the 1920s, or the Caribbean of the 1960s.

Miss Marple is also a comforting figure the reader enjoys spending time with, while maintaining a steely inner core alongside an occasionally fluffy exterior. She does her best to ensure that justice is carried out and has no time for culprits who argue they had a special reason to commit their crime, especially if that crime is murder. As one of her friends notes in the poison-pen letter case, The Moving Finger, Miss Marple’s specialism is wickedness, and nobody can beat her in tracking it down.

In many ways, Miss Marple is a contrast to the confident and even arrogant detection skills of Hercule Poirot, Christie’s first (and most prolific) detective, and Christie expressed a preference for wise Miss Marple over the perfectionist Poirot.

She also saw them as characters who existed in different worlds.

“People never stop writing to me nowadays to suggest that Miss Marple and Hercule Poirot should meet – but why should they?” she argued. “I am sure they would not enjoy it at all. Hercule Poirot, the complete egoist, would not like being taught his business by an elderly spinster.

“He was a professional sleuth, he would not be at home at all in Miss Marple’s world. No, they are both stars, and they are stars in their own right.”

By the 1960s, Christie was in her 70s, and it’s probably no coincidence she seemed more interested in the life of her older female sleuth during this decade, as Miss Marple reflected on a changing St Mary Mead with its new housing estate, before taking a trip to the Caribbean and then London’s Bertram’s Hotel.

But Christie wasn’t the only one who was interested in more Miss Marple; taking her onto the silver screen, Margaret Rutherford starred as the sleuth in four films between 1961 and 1964. Audiences and many critics adored the films, but Christie was increasingly upset to see the character of Miss Marple become such a comedic figure.

Christie and Rutherford were friendly with each other, and Christie even dedicated 1962’s The Mirror Crack’d from Side to Side to the actress. But by the time of the final film, Murder Ahoy, which was not based on Christie’s stories and saw Miss Marple dressed as an admiral, Christie was horrified and a battle with the studio ensued. Christie wished it to be made clear that the Miss Marple of these movies was undoubtedly not the same as her own creation.

This was so important that a disclaimer was added to her new books: “Featuring Miss Marple. The original character as created by Agatha Christie.” Several actresses had played the role of Miss Marple on stage, screen and radio over the years, including Gracie Fields on American television in the 1950s, but Christie wasn’t satisfied with any of the portrayals.

It was only after the author’s death aged 85 in January 1976 that there was a screen portrayal of Miss Marple that was widely considered to reflect the character as written: Joan Hickson in the BBC series that ran from 1984 to 1992.

Decades earlier, Hickson had met Christie, and during filming the actress even found an old letter from the author, in which she light-heartedly wondered if Hickson might ever play her elderly sleuth, a long time before the actress was a suitable age to play the part. It was a coincidence almost too good to be true, and the series became a huge success.

The 1980s and 1990s saw several new interpretations of Miss Marple, from Murder, She Wrote’s Angela Lansbury in a version of The Mirror Crack’d, to first lady of the American theatre, Helen Hayes, in US TV movies. Meanwhile, national treasure June Whitfield played Miss Marple herself in a successful BBC radio series. And at the turn of the 21st century there was a desire to bring her back to TV, which saw Geraldine McEwan and Julia McKenzie both playing the spinster sleuth on ITV.

Purists baulked at some of the changes, including to the identity of some killers, and even the addition of a lost love from Miss Marple’s past, but audiences tuned in worldwide to enjoy her solving mysteries again.

As for Agatha Christie, she had continued to write Miss Marple mysteries into the 1970s, with Nemesis (published in 1971) the last one to be written, although Christie had written and set aside one final case for Miss Marple in the 1940s, called Sleeping Murder.

For various reasons, it had been decided that both a Poirot novel and a Miss Marple novel were to be kept “in reserve” until the time was right for them to be published, possibly posthumously.

The final Poirot mystery, Curtain, appeared in print in 1975, just a few months before Christie’s death. While that case was clearly concerned with Poirot’s final days, Miss Marple escapes from Sleeping Murder unscathed; she seems, if anything, rather younger than she had been for years, thanks to so much time having passed since it was written. At the time, fellow crime writer Christianna Brand pondered: “Perhaps she could not bear to kill off her own grandmother?”

So, why have we spent nearly a century being interested in a spinster lady from St Mary Mead? Perhaps, more than anything, it is simply a case of envy.

Although considered to be on the margins of society, who wouldn’t wish to live Miss Marple’s life? She is a contented person with a beautiful cottage and garden, a wide circle of friends and some relatives, and a busy village life to observe.

Who wouldn’t wish to have all that, and then, perhaps, secretly hope that there might be a little crime or two that one could investigate and solve? As Miss Marple shows us, you’re never too old to become a detective.

Agatha Christie’s Marple: Expert on Wickedness, by Mark Aldridge (HarperCollins, £25) is out now. Visit expressbookshop.com or call 020 3176 3832. Free UK P&P on orders over £25