What comes to mind when you think of a witch? A woman with a pointed hat, hooked nose, green skin, long straggly hair and a broomstick? Perhaps she’s older, bad-tempered, evil to children, wreaks havoc. From Macbeth to The Wizard of Oz, that is how witches have been portrayed – and it largely continues today. It is certainly what you’ll see come Halloween. But who came up with this image? Where does it stem from and how does it play into stereotypes about women?

The idea of the evil or harmful witch comes from the late medieval and early modern period, when those who were suspected of partaking of magical rituals and conjuring spirits were seen as heretics. But this category would also include female folk healers or “wise women” who simply practised informal healthcare – for example, midwifery. As Medieval Women, a show that has just opened at the British Library in London, makes clear, such healers were sometimes viewed with contempt by (male) university-educated medical professionals. Similarly, the church condemned “acts of witchcraft” as harmful and blasphemous.

Witches were believed to be agents of the devil, who could shapeshift into animals, ride through the night on broomsticks, use magic to mess with nature, conjure storms, damage property, even murder children. While these ideas might seem bound up in fantasy, they were – by the height of the great witch-hunt, which reached its peak in the late 1500s and early 1600s – spreading like wildfire, creating widespread yet irrational fear. This was in part due to the invention of the printing press.

One of the first – and deadliest – publications to fuel this fervour was the Malleus Maleficarum (“The Hammer of Witches”). This comprehensive witchcraft manual, first published in 1486, was written by German monk Heinrich Kramer. It gathered many of these inflamed stories, claiming witches were involved in cannibalism, had sex with the devil and could cause impotence in men. Kramer said midwives offered babies to the devil. “No one does more harm to the Catholic faith,” he stated.

The Malleus was one of the main reasons that witchcraft stopped being seen as something harmless. It pushed the belief that it was solely women who practised witchcraft, a point of view even expressed its title, which chose the term “maleficarum”, as opposed to the original Latin masculine term, “maleficorum”. At the dawn of the 1500s, when witchcraft was becoming the stuff of literary discussions, artists working in print – especially in southern Germany – took note, visualising and shaping this new character. Albrecht Dürer (godson of Kramer’s publisher), drawing from classical sources, pictured the witch in two ways: young and seductive, alluring others to her coven; and haggard and old, riding backwards on a goat (a symbol of the devil).

Dürer even wrote his signature backwards on The Witch, a work from 1500, to emphasise the “disorder” of an “ordered” patriarchal culture. His student, Hans Baldung, established similar codes. He depicted witches mostly as sexualised women conspiring in groups, and his works were copied and distributed to the masses, to the Italian states and beyond. But while the images might be theatrical, exquisitely rendered and even at times humorous, the consequences for women accused of witchcraft were, sadly, very real.

Between 1450 and 1750, about 90-100,000 innocent people across Europe and North America were tortured, accused and tried. About half are thought to have been killed. Although it was believed that witches could be people of different genders and ages, including children, most of those killed (as well as stigmatised and demonised) were women.

So if you’re thinking of dressing up as an evil old green-skinned witch for Halloween, could I offer an alternative? Why not go back to those ancient times, celebrate the woman who was powerful: knowledgable about herbs, able to heal, take part in rituals and perform what seemed like magic.

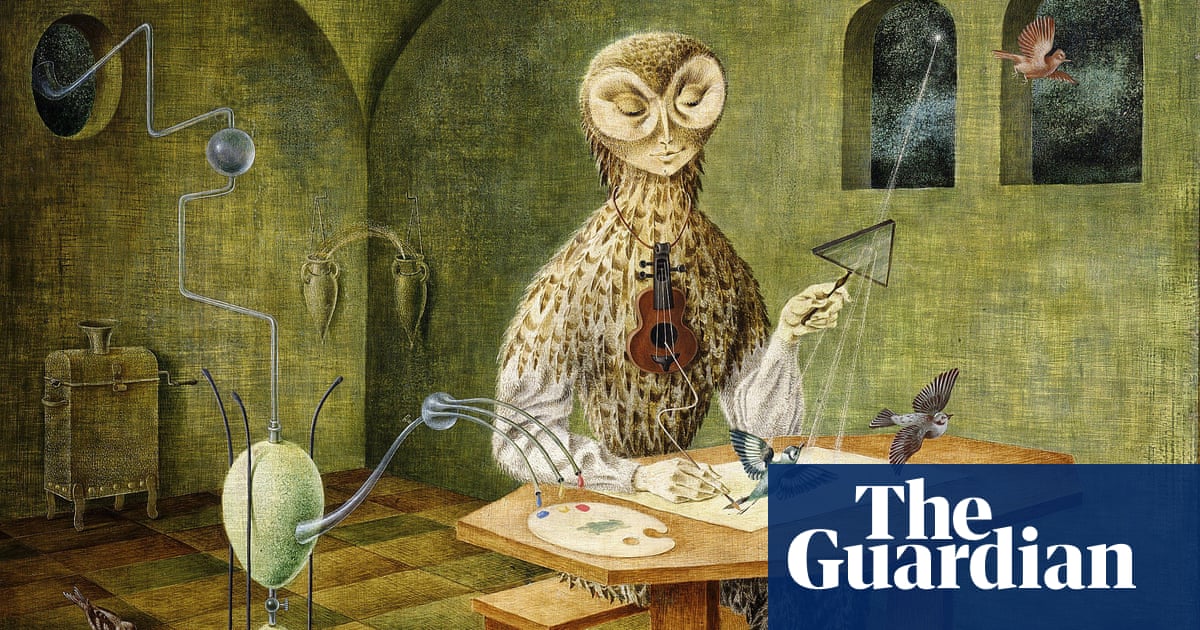

One artist who relished such characters was Remedios Varo, the Spanish-born painter who spent from 1941 until her death mostly living in Mexico City “surrounded by cats, stones, crystals and talismans”. Varo – with her best friend, the émigré surrealist Leonora Carrington – studied and practised ancient forms of witchcraft. Determined to “take back the mysteries which were ours and which were violated”, as Carrington once said, both painters delighted in creating cosmic images of formidable women shapeshifting through wonderfully imaginative worlds.

In Varo’s Creation of the Birds, from 1957, an androgynous owl-like figure shows off her ambidextrous skills, painting with one hand a bird fluttering into life before her, while in the other holding aloft a prism that refracts light from a distant star. Then there’s her Witch Going to the Sabbath, showing a hybridised figure (perhaps based on herself) wrapped from head to toe in red hair, holding a bird-like creature in her left hand, and a prism leaking light in her right.

Varo’s images feel worlds away from the witch works that helped to demonise women. They celebrate an ancient wisdom, honouring their female subjects rather than exploiting them. Varo’s witches are beautiful, emanating strength, knowledge and power.