The children of Gaza will be its future, if they are able to remain there. Starting several months into Israel’s bombardment and continuing right up until the recent ceasefire, London-based directors Jamie Roberts and Yousef Hammash made their documentary Gaza: How to Survive a Warzone by remotely instructing two local cameramen, Amjad Al Fayoumi and Ibrahim Abu Ishaiba, as they captured life inside the “safe zone” – an ever-changing, ever-dwindling area in the south-west of Gaza, designated by Israel as the place where displaced Palestinians should reside. That the cameras predominantly follow children has an unexpected double effect: it makes the film’s many deeply distressing moments all the more unbearable, yet it tinges them with some sort of hope.

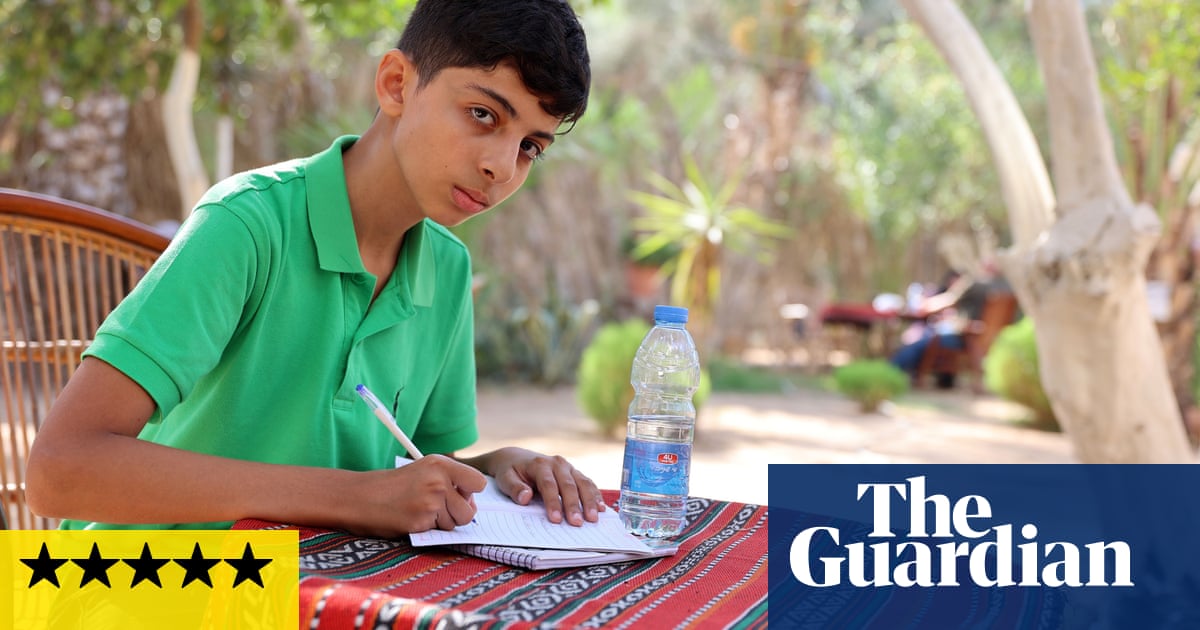

The kids are led by 13-year-old Abdullah, who acts as narrator as well as appearing on camera. “This area used to be colourful,” he says, briskly touring a scene of apocalyptic destruction in Khan Younis, where he lived in a house that sheltered 40 people before Israeli bombs turned it to dusty rubble. “Now, it’s grey.”

Abdullah maintains a wryly sunny tone as he describes how you live after you’ve lost everything, and his determination to smile while surviving is matched by 10-year-old Renad, whose method of coping with shells landing a terrifyingly short distance away is to laugh and chatter, even as the earth shakes. Renad concentrates instead on her online cooking channel: we see her recording a guide to making a dessert, apologising to viewers for having to use powdered milk. She is a natural presenter, fluent and engagingly upbeat. “They’re from all over the world,” Renad says of her growing TikTok fanbase. “If there is too long between posting videos, they check on me, thinking I got killed.”

Most remarkable is Zakaria, an indefatigable 11-year-old who chooses to spend all his time bustling around al-Aqsa, the only fully functioning hospital still standing in Gaza, having appointed himself to work as a volunteer. A fixer, porter and media liaison person, he faces a busy shift when Israeli forces raid the nearby Bureij refugee camp, killing scores of Palestinians. As civilians who have suffered blast injuries or gunshot wounds stream in, little Zakaria opens the back doors of ambulances, steers gurneys and briefs journalists, shuttling endlessly this way and that, sure-footed in the crowd.

He is asked what that mess on his hands is. “Blood from the injured and the dead,” he announces, in the disorienting matter-of-fact tone that all the children in the film share. When an overnight bombing attack leaves a crater 20ft deep elsewhere in the “safe zone”, a boy Abdullah meets as he surveys the damage is similarly sanguine. “Suddenly the sky turned red and explosions rang out,” he says, equably reporting that his uncle, aunt and cousin died. “We found the girl’s head here, along with a bone covered in flesh.”

This macabre dissonance continues as we hear the children try to square the casualties with the official statements of the Israel Defense Forces. “The Israeli army said the strikes had targeted three senior Hamas militants,” Abdullah says, carefully enunciating, of the above bombing of homeless people’s tents. Later, when missiles hit a school near al-Aqsa, causing another bloody rush at the hospital: “The Israeli army said the school was being used as a Hamas command centre.”

The film’s utterly horrific peak comes with footage, shot on 14 October 2024, which literally offers a new angle on one of the most indelible images of the war: smartphone pictures on social media meant the whole world saw 19-year-old Sha’ban al-Dalou burned alive on his hospital bed, when tents full of refugees and patients outside al-Aqsa were bombed. We are now off to one side, looking across the same scene at a right angle, focused on the rescuers who cannot penetrate the heat of the blaze. “I saw the boy burning with my own eyes,” says Zakaria. On the voiceover, Abdullah adds: “The Israeli army later said that it was a precise strike on terrorists who were operating inside a command and control centre.”

How to Survive a Warzone has unforgettable scenes of its own, such as the one where a surgeon conducts exploratory surgery on an unnamed 10-year-old to see if his injured limb can be saved; we learn the answer when we cut to the same surgeon minutes later, handing an amputated forearm to a colleague for disposal. But what lingers is what the medic says afterwards: he himself is “burning inside” with miserable anger, yet he takes comfort from his expectation that the boy will soon adjust and become “bright” again. In the face of the grimmest carnage, that light has not yet been extinguished.