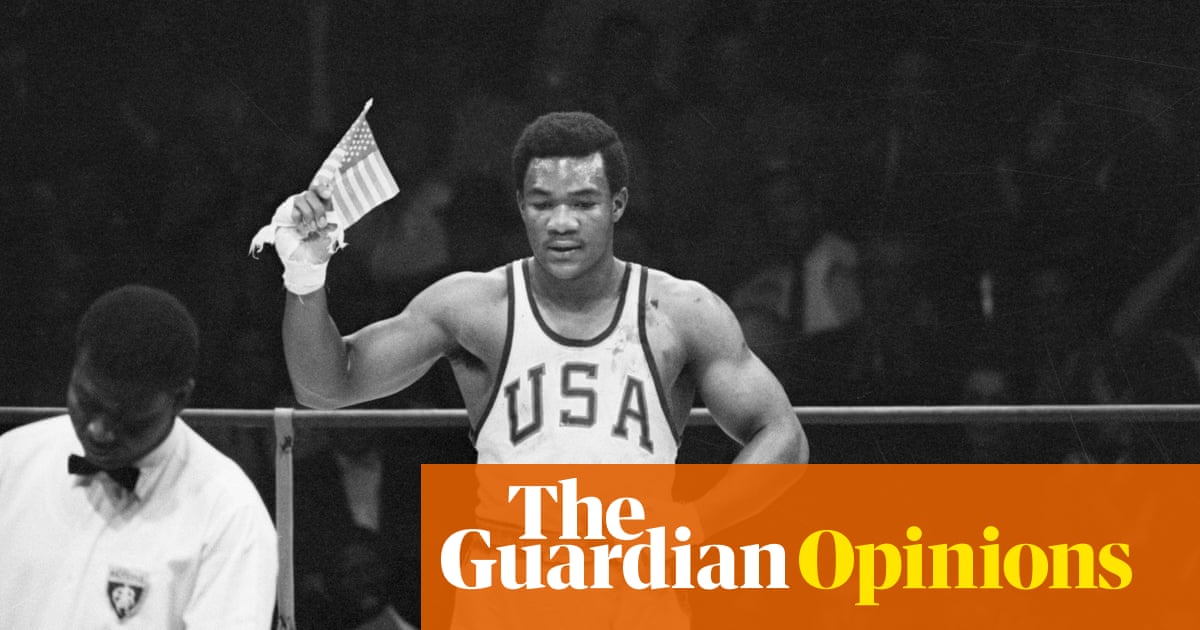

When a teenager from Texas named George Foreman waved a tiny American flag in the boxing ring after winning Olympic gold in 1968, he had little awareness of the political minefield beneath his size 15 feet. The moment, captured by television cameras for an audience of millions during one of the most volatile periods in American history, was instantly contrasted with another image from two days earlier at the same Mexico City Games: Tommie Smith and John Carlos, heads bowed and black-gloved fists raised in salute during the US national anthem, a silent act of protest that would become one of the defining visuals of the 20th century. Their message was unmistakable: a rebuke of the country that had sent them to compete while continuing to deny civil rights to people who looked like them. Their action was seen as defiant resistance, Foreman’s as deference to the very systems of oppression they were protesting.

Foreman’s flag-waving, unremarkable in almost any other context, became a lightning rod. For many, especially those aligned with the rising tide of Black Power, the gesture felt tone-deaf at best, an outright betrayal at worst. How could a young Black man, representing a country still brutalizing his own people, celebrate it so enthusiastically? But that reading, while emotionally understandable amid the fevered upheaval of 1968, misses something deeper – about Foreman, about patriotism, and about the burden of symbolic politics laid on the shoulders of Black athletes.

To understand the backlash the 19-year-old Foreman faced in the context of 1968, particularly from within the Black community, is to understand the mood of that year: a procession of funerals and fires, of uprisings in Detroit and Newark, of young people trading dreams of integration for the sharp rhetoric of militant self-determination. Dr Martin Luther King Jr had been gunned down in Memphis just months earlier. Black Power was no longer a whisper in back rooms or college classrooms – it had become a rallying cry, a style, a stance. And in that charged atmosphere, there seemed to be only one acceptable way to be Black and politically conscious: with fist raised, spine straight, voice sharpened by injustice.

In that climate, Smith and Carlos’s silent, defiant protest was seismic. They paid dearly for it – expelled from the Games, vilified at home and exiled from professional opportunity for years. They were heroes, then and now. But the demand for unity behind that particular kind of protest was strong. To many, in that moment, there was only one acceptable way to be Black and political. Foreman’s flag violated that code. It did not speak the language of protest. It did not name the enemy. And so, some saw it as a profound misstep.

Foreman has long insisted that there was no statement embedded in the flag he waved. “I didn’t know anything about [the protest] until I got back to the Olympic Village,” he said years later. “I didn’t wave the flag to make a statement. I waved it because I was happy.” But in 1968, happiness was a political act, and its symbols did not float innocently above the fray. To wave the American flag in that moment – as tanks rolled through Chicago, as King’s assassination still echoed in the national conscience – was to wade, however unknowingly, into a pool already churning with tension and meaning.

That kind of apolitical happiness wasn’t just suspicious – it was infuriating to those risking everything to challenge the systemic racism at the foundation of American society. The fact that the mainstream white media embraced Foreman as a “good” Black athlete in contrast to Smith and Carlos only deepened the rift. He was positioned, perhaps unintentionally, as the safe symbol of patriotism, the counter-image to fists in the air.

And yet Foreman’s story was never simple. He grew up poor in Houston’s Fifth Ward, a tough and segregated neighborhood. He found boxing through the Job Corps, a federal anti-poverty program. For Foreman, the flag didn’t represent a government that had failed him – it represented a country that had offered him a way out. His patriotism was anything but performative; it was deeply personal.

Too often, different experiences of Blackness are mistaken for ideological betrayal. Not every expression of pride in America is a denial of its sins. Sometimes it’s a hard-earned survival mechanism. For Foreman, the flag may have symbolized escape, opportunity and the dream that somehow, in spite of it all, he belonged.

Still, the criticism followed him, stubborn and sharp. He was branded an Uncle Tom, accused of pandering to white America, made to feel, by his own account, unwelcome in many Black spaces. His response was not to explain but to retreat. In the ring, he became a fearsome presence – angry, sullen and distant. Outside it, he said little, and seemed to carry a quiet fury beneath the surface. When he lay waste to Joe Frazier in 1973, knocking him down six times in two rounds to claim the heavyweight crown, he celebrated not with a grin but with a kind of grim inevitability. He looked less like a champion than an avenger.

But narratives have a way of bending, especially in American life, and Foreman’s eventually did. Not long after losing it all with his crushing loss to Muhammad Ali in Zaire the following year – a defeat that humbled and haunted him – he disappeared for a decade. He found God, became a preacher, opened a youth center. When he returned to boxing in the late 1980s, older, heavier and unfashionably gentle, the public met him with something approaching affection. He smiled now. He cracked jokes. He appeared on talk shows. And when, at 45 years old, he reclaimed the heavyweight title in one of the sport’s most unlikely comebacks, it felt not like redemption but reinvention.

The same man who once waved the flag and was scorned for it now hawked millions of countertop grills bearing his name. He starred in a prime-time network TV sitcom. He named all five of his sons George. He leaned into the myth and made it charming. In doing so, he reshaped the cultural meaning of his image – from the quiet bruiser to the joyful elder statesman, a symbol of resilience, reinvention and a kind of pragmatic hope. There’s a credible argument that he succeeded Bill Cosby as America’s dad.

We should not forget, nor flatten, the radical clarity of Smith and Carlos’s gesture. Nor should we mistake Foreman’s act for anything it was not. But perhaps we can now make room for both. Black patriotism has never been a monolith; it has always contained tension, ambiguity, contradiction. Some express it through protest, others through perseverance. A fist raised, a flag waved – both can be acts of love, not of submission, but of insistence: that the country be made to live up to its promise. And in a nation that often demands that Black people perform either rage or gratitude, George Foreman dared to be something else: complex.

The enduring lesson of 1968 is not that one form of Black political expression is inherently more valid than another, but that the burden placed on Black athletes to symbolize a collective experience is often impossibly heavy. Every gesture is scrutinized. Every silence is interpreted. Every celebration is suspect. In that sense, Foreman’s flag was never just about joy – it was about the impossibility of being apolitical in a body already politicized by history. He did not salute a perfect America. He saluted the possibility of one.